How Telemedicine Can Prop Up Underserved Communities

Authored by Ayesha Rajan, Research Analyst at Altheia Predictive Health

Introduction

Seventeen years ago, The Institute of Medicine published a report titled “Unequal Treatment” in which they researched how racial and ethnic minority patients experience disparities within the healthcare system. The result of this research was to encourage physicians, nurses and providers to find ways to address racial disparities in practice. However, when The Institute of Medicine decided to follow up on their initial report ten years later, they found that little had been done to address the problem. So, the problem remains and is one we must address. Perhaps the answer, or at least part of it, lies in telemedicine. Telemedicine is often touted as a way to increase access to medical care among underserved communities and in this article, we will delve into whether or not that holds true.

Current Problem

The Commonwealth Fund states that “Compared with white [patients], members of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventative health services, often receive lower-quality care [and]… have worse health outcomes for certain conditions” (Hostetter). This all remains true even when insurance status, income, age and severity of condition are held constant as variables. In fact, Dayna Bowen Matthew explored why this might be the case in her book “Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Healthcare.” She found that many physicians who took the Implicit Association Test (a test that measures a person’s implicit racial biases) exhibited a significant amount of bias which, even if subconscious, can result in inconsistent treatment of patients (Bridges).

Telemedicine as a Solution

NCBI performed a study in which they evaluated the effectiveness of stroke care amongst White, Black and Hispanic patients in Texas in physical hospital settings and in using telemedicine services. The motivation for the study stems from reported disparities in acute stroke care treatment for underserved communities and hoped to observe if access to telemedicine services affected any of these disparities. The study begins by noting that racial and ethnic minorities have a higher chance of incidence for strokes than non-minorities which can account, in part, for the increased morbidity rate in minority groups. However, they go on to add that the higher morbidity rate can also be attributed to the fact that minorities often receive “reduced or delayed activation of emergency medical services [and] longer wait times for evaluations and neurologic consultation… As a consequence, fewer racial and ethnic minorities receive tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)” which is the only approved medical therapy for acute ischaemic strokes (NCBI). The study concluded that in Texas, telemedicine services for stroke patients increased treatment availability to an additional 1.5 million citizens without widening the racial disparity gap. The authors add that part of the reason that telemedicine has been so impactful in this particular area of treatment is, in part, because many stroke treatment centers are found in urban areas and difficult to access for the people living in rural areas where many people are still at risk of having a stroke. Furthermore, they add that telemedicine has the capability to reduce the disparity in tPA administration by getting rid of geographic constraints that can work against those living further from treatment centers.

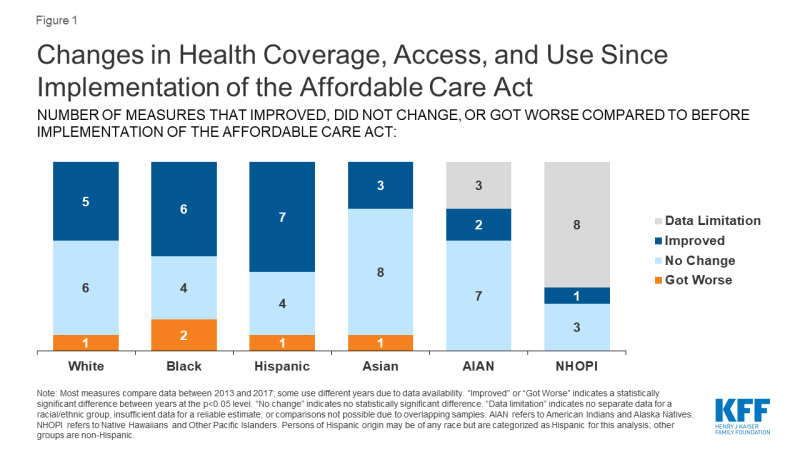

Kaiser Family Foundation picks up where NCBI left off in their study of the effects of telemedicine on minority groups and found that, not only were minorities not negatively impacted by the introduction of telemedicine, every single racial and ethnic group experienced improvements in their access to healthcare:

They note that young Black and Hispanic patients still experience disparities in access to healthcare, but the fact that those disparities were narrowed means that the adoption of telemedicine is a step in the right direction.

Conclusion

The biggest appeal of telemedicine for underserved communities is to engage those without reliable or convenient access to healthcare in maintaining their wellbeing. The studies discussed in this article show that telemedicine has the power to do just that by increasing access to healthcare and reducing the disparities in treatment of racial and minority groups. Ultimately, telemedicine still has its challenges in its use as a medical tool but the fact that people who had no access at all to healthcare have seen improvements means that those challenges are worth tackling.

Works Cited

Artiga, Samantha, and Kendal Orgera. “Key Facts on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity.” KFF, 13 Nov. 2019, www.kff.org/disparities-policy/report/key-facts-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/.

Bridges, Khiara. “Implicit Bias and Racial Disparities in Health Care.” American Bar Association, www.americanbar.org/groups/crsj/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/the-state-of-healthcare-in-the-united-states/racial-disparities-in-health-care/.

Hostetter, Martha, and Sarah Klein. “In Focus: Reducing Racial Disparities in Health Care by Confronting Racism.” Commonwealth Fund, 27 Sept. 2018, www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2018/sep/focus-reducing-racial-disparities-health-care-confronting.

Lyerly, Michael J, et al. “The Effects of Telemedicine on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to Acute Stroke Care.” Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Mar. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4948296/.